“Stately, plump Buck Mulligan came from the stairhead, bearing a bowl of lather on which a razor and a mirror lay crossed” etc etc

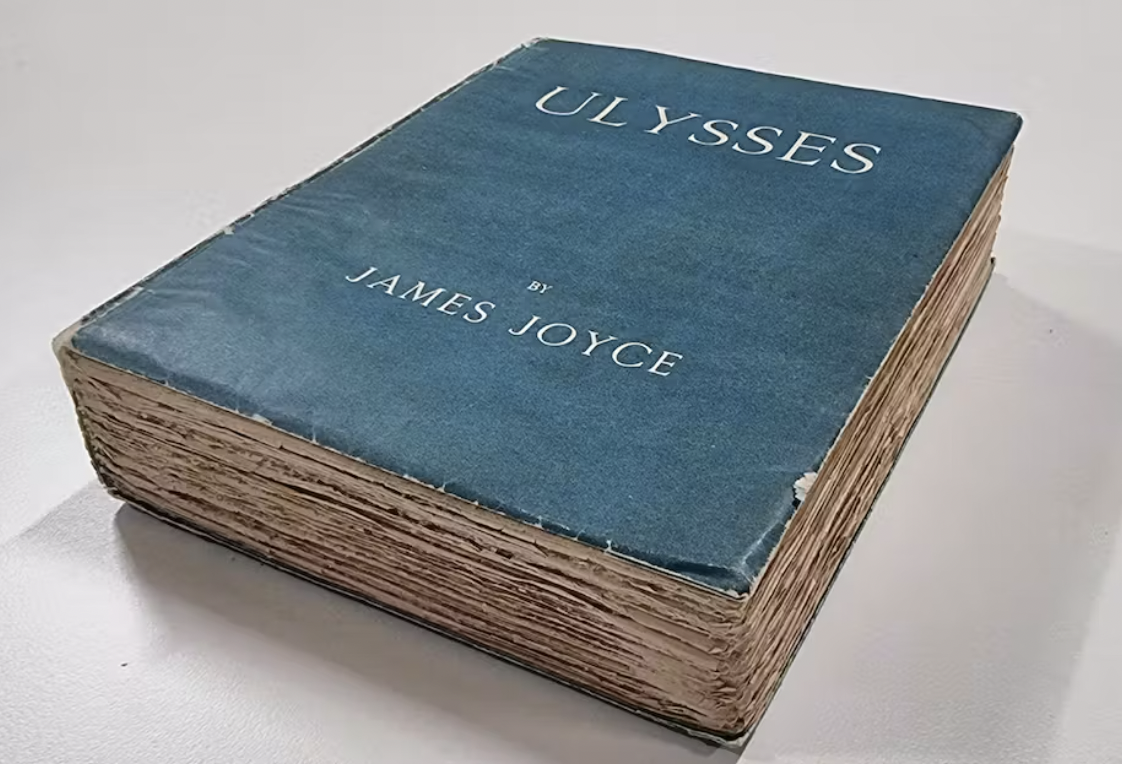

James Joyce’s Ulysses – published in 1922, banned, controversial, “ground-breaking”. I have many, many times heard the novel extolled as one of the greatest feats of literature in history, number one in the charts (yes, literally, according to “very serious” charts by some “very serious” commentators), so good that, in the words of someone I spoke with, there isn’t much point in trying to write novels any more, since you cannot achieve what Joyce did.

Do I agree? No. I read Ulysses when studying English Literature – and I liked it in some ways, and yes, I actually finished reading it – not always the case (and anyway, I don’t believe in reading novels if you are really not enjoying them. A waste of time.)

There are some rather beautiful passages; there is a strong sense of location – on one single day in Dublin as the main character, Leopold Bloom, a salesman, roams around, while being cuckolded. Yes, it has a masturbation scene and Bloom sits on the toilet etc etc.

But the book is mired in pretentiousness and self-consciousness. It’s very, very self-consciously important. The whole story has, of course from its title and various allusions, reference points to classical antiquity. The other main character is called Stephen Dedalus for Christ’s sake! (Daedulus the mythical Greek inventer and sculptor). I mean really? The sheer po-faced seriousness of that name! The character is based on Joyce himself, unsurprisingly.

The novel is also very, very self-consciously clever. There are constant experiments – oh, let’s write a chapter like newspaper headlines? Or a chapter like an absurdist piece of theatre? You got it!

Not a great deal happens in the novel of any consequence. But it’s massively and poetically recorded. There isn’t a compelling reason to care about the characters. Yes, I had some interest. We are inside someone’s head a lot, but the characters tend towards sanctimonious statements on the state of the world or art, or mildly interesting thoughts about what they are concerned with in the moment. But I feel many other novels get to the heart of characters and interesting issues much more quickly, much more profoundly and much more movingly. Take any novel by Robert Harris for example. I think he’s an unquestionably superior writer to Joyce. But he writes in a mainstream style – and tells stories for God’s sake – so therefore he can’t be “very serious” and “very important.”

The problem is that Ulysses has been exalted to a pinnacle. It’s seen as the ultimate example of great literature. And it’s led to an awful lot of dead-end literary emulations – with writers earnestly putting out their very serious, stream-of-consciousness narratives. Because that must be the way we write from now on, right? In fact, it’s the only way to write that counts any more.

In short, Ulysses is too concerned with its own seriousness, too self-consciously striving to be clever, too little concerned with telling a good story to actually be a good novel.

In the literary pantheon it’s achieved the status of Citizen Kane in the movie pantheon. Another example of a not very good product somehow being fossilized into greatness. It’s not a very good film, and Ulysses is not a very good novel.

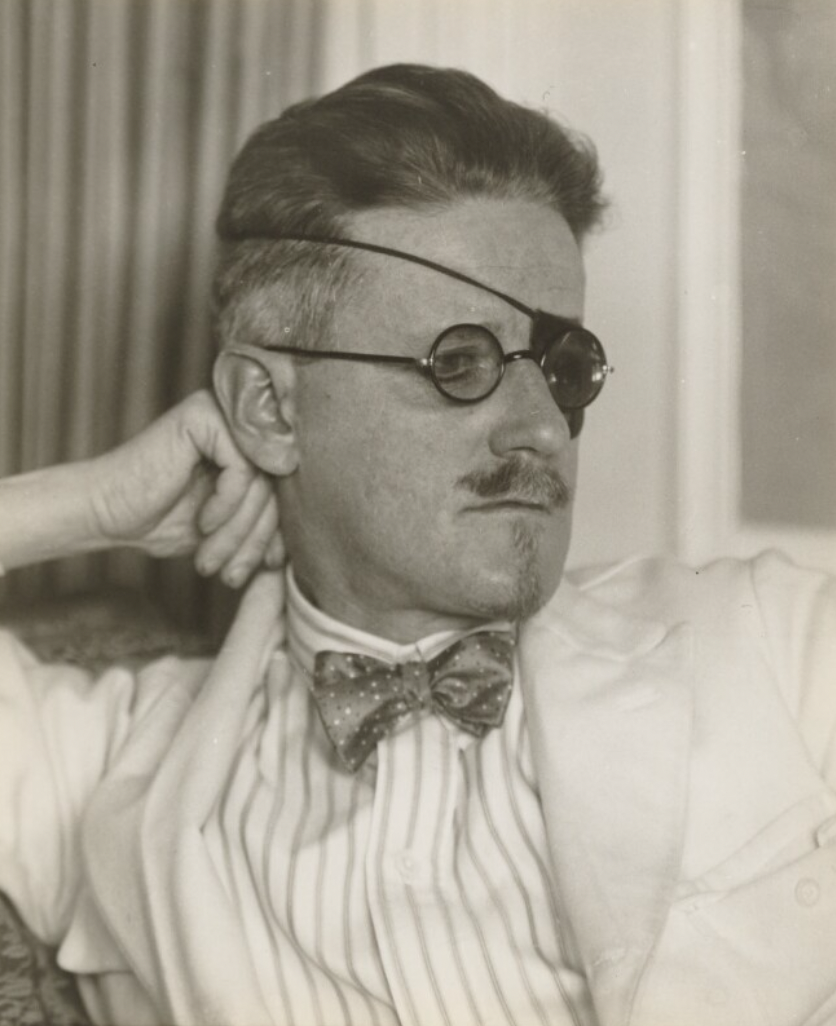

Although I studied English literature, (in a negligent, disorganized and extremely limited way – since I didn’t do much academic work) I am not big on literary criticism. Most of it is unreadable. But there are exceptions. DH Lawrence is an exception.

His literary criticism is entertaining, very well-informed and usually spot on – and frequently funny. I have to admit that Lawrence puts the case against Joyce much more pungently than I can.

I’ll let him speak for himself.

“Is the novel on his death-bed, old sinner? Or is he just toddling round his cradle, sweet little thing? Let us have another look at him, before we decide.

There he is, the monster with many faces, many branches to him like a tree: the modern novel. And he is almost dual like a Siamese twin. On the one hand, the pale-faced, high-browed, earnest novel which you have to take seriously: on the other, that smirking, rather plausible hussy, the popular novel.

Let us just for the moment feel the pulses of Ulysses and of Miss Dorothy Richardson and Monsieur Marcel Proust, on the earnest side of Briareus; on the other, the throb of The Sheik and Mr Zane Grey, and, if you will, Mr Robert Chambers and the rest…

So there you have the “serious” novel, dying in a very long-drawn-out fourteen-volume death-agony, and absorbedly, childishly interested in the phenomenon. “Did I feel a twinge in my little toe, or didn’t I?” asks every character in Mr Joyce or Miss Richardson or Monsieur Proust. “Is the odour of my perspiration a blend of frankincense and orange pekoe and boot-blacking, or is it myrrh and bacon-fat and Shetland tweed?”

The audience round the death-bed gapes for the answer. And when, in a sepulchral tone, the answer comes at length, after hundreds of pages: “It is none of these, it is abysmal chloro-coryambasis,” the audience quivers all over, and murmurs: “That’s just how I feel myself.”

Which is the dismal, long-drawn-out comedy of the death-bed of the serious novel. It is self-consciousness picked into such fine bits that the bits are most of them invisible, and you have to go by smell. Through thousands and thousands of pages Mr Joyce and Miss Richardson tear themselves to pieces, strip their smallest emotions to the finest threads, till you feel you are sewed inside a wool mattress that is being slowly shaken up, and you are turning to wool along with the rest of the woollyness.

It’s awful. And it’s childish. It really is childish, after a certain age, to be absorbedly self-conscious. One has to be self-conscious at seventeen: still a little self-conscious at twenty-seven; but if we are going it strong at thirty-seven, then it is a sign of arrested development, nothing else. And if it is still continuing at forty-seven, it is obvious senile precocity.

And there’s the serious novel: senile precocious. Absorbedly, childishly concerned with What I am. “I am this, I am that, I am the other. My reactions are such, and such, and such. And oh Lord, if I liked to watch myself closely enough, if I liked to analyse my feelings, minutely, as I unbutton my pants, instead of saying crudely I unbuttoned them, then I could go on to a million pages, instead of a thousand. In fact, the more I come to think of it, it is gross, it is uncivilised bluntly to say: I unbuttoned my pants. After all, the absorbing adventure of it! Which button did I begin with?—?” etc. etc. (LOL – editor)

The people in the serious novels so absorbedly concerned with themselves and what they feel and don’t feel, and how they react to every mortal trouser-button; and their audience as frenziedly absorbed in the application of the author’s discoveries to their own reactions; “that’s me! that’s exactly it! I’m just finding myself in this book!”—why, this is more than death-bed, it is almost post mortem behaviour.

Some convulsion or cataclysm will have to get the serious novel out of its self-consciousness. The last great war made it worse. What’s to be done?”

I can’t beat that for a commentary.

Leave a comment