My opinion on D.H. Lawrence is inescapably mixed. He’s one of my favourite writers, and there are passages in his works that no other writer could have written (in a good sense).

But on the other side of the ledger, Lawrence went through a fascist period for several years, often rejected science and rationality, and Bertrand Russell concluded that his ideas led straight to Auschwitz. That last judgement is very harsh, much as I admire Russell. The two men were friends for a while during WW1, then quarreled violently.

At one point, Lawrence wrote this to Russell (ouch!):

Your basic desire is the maximum of desire of war, you are really the super-war-spirit. What you want is to jab and strike, like the soldier with the bayonet, only you are sublimated into words. And you are like a soldier who might jab man after man with his bayonet, saying “this is for ultimate peace”.

Strangely, they almost had the same familiar name: Bert, from Lawrence’s second name, Herbert, and Bertie from Bertrand. Bert and Bertie – what an incongruous couple.

Phallus

But then there’s also this question: was Lawrence a champion of the phallus and basically believed that women should submit to men? There are critics like Kate Millett, writing in the 70s, who argue that is the case. More recently, there have been women writers and critics, like Frances Wilson and Lara Feigel, who dispute this view and argue that Lawrence’s writing on the relationship between the sexes is vital and engaging and allows for a balance of perspectives.

I’m with the latter group.

Then there’s also the other way Lawrence is mixed – in the quality of his work itself.

There is, in my opinion, some sublimely good work, but there are also middling and outright bad works by him. Some of his novels for example, like The Plumed Serpent and Aaron’s Rod, which reflect his fascist period, are definitely bad.

Not a few commentators, from Orwell on to the present, argue that Lawrence’s best work isn’t in his novels, it’s in his short stories. I agree that he is a master of the short story, and there are many, many fabulous examples, and some wonderful novellas, like The Fox: (extract)

The young man — or youth, for he would not be more than twenty — now advanced and stood in the inner doorway. March, already under the influence of his strange, soft, modulated voice, stared at him spellbound. He had a ruddy, roundish face, with fairish hair, rather long, flattened to his forehead with sweat. His eyes were blue, and very bright and sharp. On his cheeks, on the fresh ruddy skin were fine, fair hairs, like a down, but sharper. It gave him a slightly glistening look. Having his heavy sack on his shoulders, he stooped, thrusting his head forward. His hat was loose in one hand.

He stared brightly, very keenly from girl to girl, particularly at March, who stood pale, with great dilated eyes, in her belted coat and puttees, her hair knotted in a big crisp knot behind. She still had the gun in her hand. Behind her, Banford, clinging to the sofa-arm, was shrinking away, with half-averted head.

‘I thought my grandfather still lived here? I wonder if he’s dead.’

‘We’ve been here for three years,’ said Banford, who was beginning to recover her wits, seeing something boyish in the round head with its rather long, sweaty hair.

‘Three years! You don’t say so! And you don’t know who was here before you?’

‘I know it was an old man, who lived by himself.’

‘Ay! Yes, that’s him! And what became of him then?’

‘He died. I know he died.’

‘Ay! He’s dead then!’

The youth stared at them without changing colour or expression. If he had any expression, besides a slight baffled look of wonder, it was one of sharp curiosity concerning the two girls; sharp, impersonal curiosity, the curiosity of that round young head. But to March he was the fox.

Whether it was the thrusting forward of his head, or the glisten of fine whitish hairs on the ruddy cheek-bones, or the bright, keen eyes, that can never be said: but the boy was to her the fox, and she could not see him otherwise.

But I think some of his novels are also really good and among his best work, though I also feel even these best novels are still flawed. I’m thinking of Women in Love, Lady Chatterley’s Lover and Sons and Lovers. (more on this later)

Then there is Lawrence’s poetry – much of it absolutely marvelous – like The Snake: (extract)

A snake came to my water-trough

On a hot, hot day, and I in pyjamas for the heat,

To drink there.

In the deep, strange-scented shade of the great dark carob-tree

I came down the steps with my pitcher

And must wait, must stand and wait, for there he was at the trough before me.

He reached down from a fissure in the earth-wall in the gloom

And trailed his yellow-brown slackness soft-bellied down, over the edge of the stone trough

And rested his throat upon the stone bottom,

And where the water had dripped from the tap, in a small clearness,

He sipped with his straight mouth,

Softly drank through his straight gums, into his slack long body,

Silently.

Someone was before me at my water-trough,

And I, like a second comer, waiting.

He lifted his head from his drinking, as cattle do,

And looked at me vaguely, as drinking cattle do,

And flickered his two-forked tongue from his lips, and mused a moment,

And stooped and drank a little more,

Being earth-brown, earth-golden from the burning bowels of the earth

On the day of Sicilian July, with Etna smoking.

And as well as this, there are a great many interesting, dynamic essays. He was very prolific. He often had to churn out essays to keep life and soul together, since he didn’t have much money. (extract from Why the Novel Matters):

We have curious ideas of ourselves. We think of ourselves as a body with a spirit in it, or a body with a soul in it, or a body with a mind in it. Mens sana in corpore sano. The years drink up the wine, and at last throw the bottle away: the body, of course, being the bottle.

It is a funny sort of superstition. Why should I look at my hand, as it so cleverly

writes these words, and decide that it is a mere nothing compared to the mind that directs it? Is there really any huge difference between my hand and my brain?—or my mind? My hand is alive, it flickers with a life of its own. It meets all the strange universe, in touch, and learns a vast number of things, and knows a vast number of things. My hand, as it writes these words, slips gaily along, jumps like a grasshopper to dot an i, feels the table rather cold, gets a little bored if I write too long, has its own rudiments of thought, and is just as much me as is my brain, my mind, or my soul. Why should I imagine that there is a me which is more me than my hand is? Since my hand is absolutely alive, me alive.

Whereas, of course, as far as I am concerned, my pen isn’t alive at all. My pen isn’t me alive. Me alive ends at my finger-tips.

Whatever is me alive is me. Every tiny bit of my hands is alive, every little freckle and hair and fold of skin. And whatever is me alive is me. Only my finger-nails, those ten little weapons between me and an inanimate universe, they cross the mysterious Rubicon between me alive and things like my pen, which are not alive, in my own sense.

So, seeing my hand is all alive, and me alive, wherein is it just a bottle, or a jug,

or a tin can, or a vessel of clay, or any of the rest of that nonsense? True, if I

cut it it will bleed, like a can of cherries. But then the skin that is cut, and the

veins that bleed, and the bones that should never be seen, they are all just as alive as the blood that flows. So the tin can business, or vessel of clay, is just bunk.

Novels

Returning to his novels, it’s interesting that numerous critics – almost a consensus – say that The Rainbow is his best novel. I think The Rainbow is rather tedious, but with some good passages – especially the section where Ursula is struggling to contain a class while she trains as a teacher – which is no doubt based on Lawrence’s own experiences of teaching at a school in Croydon, and is spot-on about the struggle of wills that can take place in any class. But overall, it’s a bit of a hard read, in my experience – too ambitious in taking on too many characters and stories, and thus becomes a rather boring parade of descriptions, family after family, relationship after relationship. The opening is turgid and not very readable. Lawrence was clearly aiming for a multi-generational epic, but it fails to lift off.

How does this kind of thing happen? Sometimes I think a majority of critics are unhelpful fools (yes, that’s a bit of a Lawrentian-style statement) But honestly! There’s a lot of pretentiousness. My strong suspicion is that too many critics say what they think they ought to say, not daring to admit what they actually like and dislike.

This happens all the time. I am an admirer of John Updike for example, but most of the critics say that the ‘Rabbit” series is his best work. Not me. It’s a tedious read, trying much too hard, in my opinion, to be the “Great American Novel.” I much prefer many of his other works, like The Centaur, The Witches of Eastwick and the Bech series.

And then to Jane Austen – I’m a massive fan. But again, there seems to be a large body of critics who assert that Emma is possibly her finest novel. I strongly disagree, finding Emma a bit unsatisfying, not a bad novel, but a tad dull in places. Give me Pride and Prejudice, Sense and Sensibility, Persuasion and Mansfield Park any day.

Don’t listen to those damn critics! Why do they promote writers’ dullest books?

Women in Love, Lawrence’s next novel after The Rainbow (in fact a sequel) is far more dynamic and exciting. It’s a novel infused with war, but barely mentions war, written during World War 1. It’s about big issues: the crisis that Lawrence sees in relationships, the deadening of the human spirit under industrialization, the death struggle between the classes in England and so on.

Lawrence’s intent was not to write about the known and “conscious” aspect of human relationships, but the hidden, deeper, inorganic core of beings (as he framed it) – the unconscious processes driving human behaviour. He railed against seeing all human relationships as being defined in the sphere of rationality and conscious knowledge. I don’t completely agree with this viewpoint by any means, but it’s powerful, unusual and interesting. And his recreation of the relationships between the main characters is often fascinating and visceral. (extract):

But even as she lay in fictitious transport, bathed in the strange, false sunshine of hope in life, something seemed to snap in her, and a terrible cynicism began to gain upon her, blowing in like a wind. Everything turned to irony with her: the last flavour of everything was ironical. When she felt her pang of undeniable reality, this was when she knew the hard irony of hopes and ideas.

She lay and looked at him, as he slept. He was sheerly beautiful, he was a perfect instrument. To her mind, he was a pure, inhuman, almost superhuman instrument. His instrumentality appealed so strongly to her, she wished she were God, to use him as a tool. And at the same instant, came the ironical question: ‘What for?’

She thought of the colliers’ wives, with their linoleum and their lace curtains and their little girls in high-laced boots. She thought of the wives and daughters of the pit-managers, their tennis-parties, and their terrible struggles to be superior each to the other, in the social scale. There was Shortlands with its meaningless distinction, the meaningless crowd of the Criches. There was London, the House of Commons, the extant social world. My God!

Young as she was, Gudrun had touched the whole pulse of social England. She had no ideas of rising in the world. She knew, with the perfect cynicism of cruel youth, that to rise in the world meant to have one outside show instead of another, the advance was like having a spurious half-crown instead of a spurious penny.

The whole coinage of valuation was spurious. Yet of course, her cynicism knew well enough that, in a world where spurious coin was current, a bad sovereign was better than a bad farthing. But rich and poor, she despised both alike.

I find there are also flaws. The thing is – and Lawrence reportedly resisted this strongly – he needed a strong editor to cut out some of the excesses in his writing. Women in Love would be an even better book if an editor had insisted on taking out one purple passage in particular – the bit about the oft-quoted “suave loins of darkness”. Yes, it does sound pretty absurd, and it’s been much mocked. Essentially, it’s an over-written and badly written purple passage, about three pages long. The thing is, he did relationships elsewhere in the book much better, on a similar theme, and the writing is far superior. Oh editor, you should have taken that passage out!

Aside from this lapse, I find Women in Love a fascinating and engaging novel, far better than its prequel The Rainbow.

Then there’s Lady Chatterley’s Lover. I re-read it recently and was struck by how damn good the book is, with its brilliant, big picture descriptions of society – for example, the intellectual and artistic communities in England, and then the inner and outer struggle between a husband and wife. As ever with Lawrence, there are vivid descriptions of the landscape in the midlands, where he grew up:

Little gusts of sunshine blew, strangely bright, and lit up the celandines at the wood’s edge, under the hazel-rods, they spangled out bright and yellow. And the wood was still, stiller, but yet gusty with crossing sun. The first windflowers were out, and all the wood seemed pale with the pallor of endless little anemones, sprinkling the shaken floor. ‘The world has grown pale with thy breath.’ But it was the breath of Persephone, this time; she was out of hell on a cold morning.

Cold breaths of wind came, and overhead there was an anger of entangled wind caught among the twigs. It, too, was caught and trying to tear itself free, the wind, like Absalom. How cold the anemones looked, bobbing their naked white shoulders over crinoline skirts of green. But they stood it. A few first bleached little primroses too, by the path, and yellow buds unfolding themselves. The roaring and swaying was overhead, only cold currents came down below.

Connie was strangely excited in the wood, and the colour flew in her cheeks, and burned blue in her eyes. She walked ploddingly, picking a few primroses and the first violets, that smelled sweet and cold, sweet and cold. And she drifted on without knowing where she was.

And I think the relationships between Lady Chatterley (Connie), her husband and Mellors the gamekeeper are brilliantly done. The book has been much lampooned and criticized, to the extent that you find commentators saying it’s “embarrassing.” I don’t find it so. I think the novel has been overtaken and encircled by its history – the famous obscenity trial in the UK, the focus on the swear words that Lawrence deliberately used, so tired had he become of censorship – (The Rainbow was banned, his paintings were seized and so on). He wrote in “fuck,” “cunt” and “shit” in a deliberate attempt to reclaim the words as real, physical references to actual human relationships.

Yes, there’s one ugly passage of about three pages, where Mellors talks in a rather horrible way about a previous relationship, referring to his previous wife’s “beak,” “down there” – presumably meaning her clitoris. It’s nasty and misogynistic and an editor would have done well just to take it out. But even here, the assumption that this is simply Lawrence speaking is questionable – Connie argues with Mellors about his view of women. And Mellors is a character in Lawrence’s book, not Lawrence himself. Yes, Macbeth murders the king, but this does not mean that Shakespeare is in favour of murdering kings.

Lawrence has many characters express opinions that he doesn’t share or he also has them express some of his own thoughts and feelings in a much more extreme, absolutist and sometimes repugnant way. I think his process was to let it all out – let out the underlying thoughts, feelings, ideas – let them play out and be contradicted in the novel. Let the battle commence! No censorship of thoughts and feelings! Still, I would happily have had that section edited out.

More importantly, I say that the relationship between Mellors and Connie, and the marriage between Connie and Clifford, are very richly and sensitively described. Some of Lawrence’s best writing is found in this book. So I think the public perception of the novel is often not at all based on people actually reading the book, but on other people’s commentaries and second-hand reporting. Sadly, the novel has become, for some, a by-word for smutty sex, which is the very last thing that Lawrence was aiming at – and he certainly didn’t create “smutty sex” in the novel. They’ve “done dirt on sex”, he wrote elsewhere, and many people have indeed “done dirt” on the novel, or at least an imagined simulacrum of the novel.

I simply think it’s a really good read. Mellors and Connie are left in a kind of half-space – they’ve found a real connection, but in practice they are struggling to make a life together. It ends on a reflective, wistful and rather sober note.

Then there’s Sons and Lovers. I re-read that too recently. I think the description of working-class life and family dynamics is incredibly powerful and has a sense of truth and authenticity. Lawrence of course knew this first- hand – he grew up the son of a miner, and had to work in a factory as teenager, before getting a teaching job. It was only Lawrence’s brilliance, and his scholarliness, that got him into the world of literature and the arts.

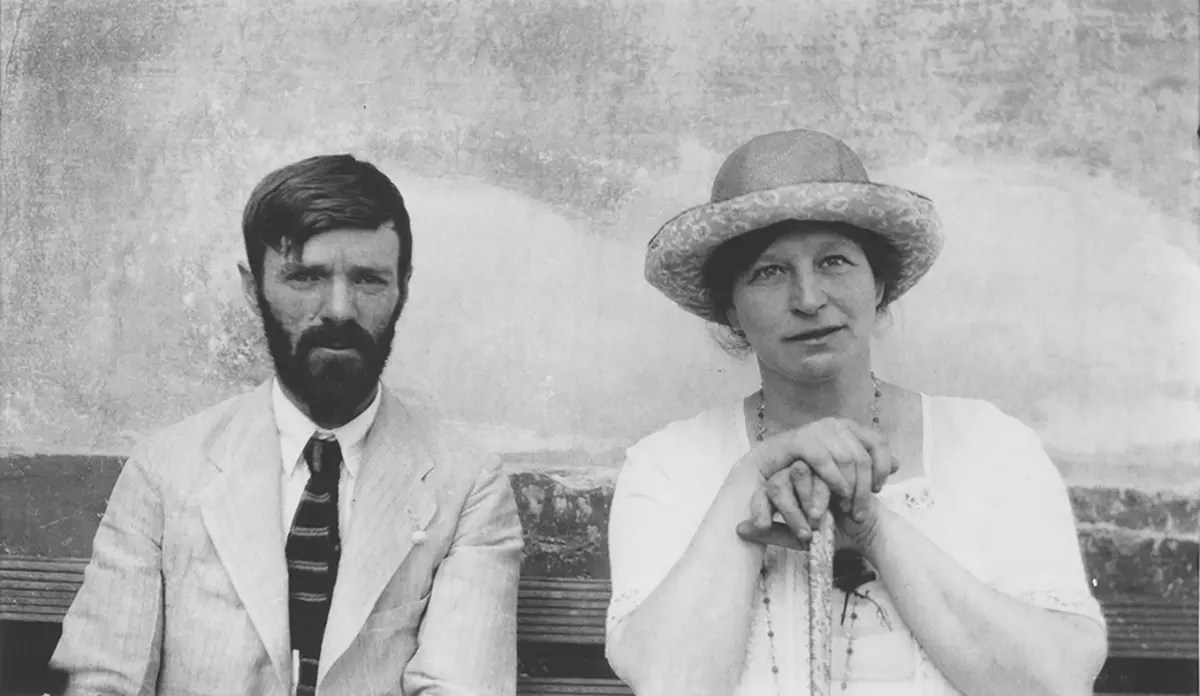

(Lawrence is the young boy standing between his parents.)

I have never read anything as good in fiction on working-class life.

The dynamics between the main character Paul, his mother, and his lovers are very well developed and interesting. Again, Lawrence seems to have the knack of touching the raw kernel of human relationships, the flame – the hidden, inorganic, root of them if you like – which makes his descriptions extremely vivid.

Walter Morel was, at this time, exceedingly irritable. His work seemed to exhaust him. When he came home he did not speak civilly to anybody. If the fire were rather low he bullied about that; he grumbled about his dinner; if the children made a chatter he shouted at them in a way that made their mother’s blood boil, and made them hate him.

On the Friday, he was not home by eleven o’clock. The baby was unwell, and was restless, crying if he were put down. Mrs. Morel, tired to death, and still weak, was scarcely under control.

“I wish the nuisance would come,” she said wearily to herself. The child at last sank down to sleep in her arms. She was too tired to carry him to the cradle. “But I’ll say nothing, whatever time he comes,” she said. “It only works me up; I won’t say anything. But I know if he does anything it’ll make my blood boil,” she added to herself.

She sighed, hearing him coming, as if it were something she could not bear. He, taking his revenge, was nearly drunk. She kept her head bent over the child as he entered, not wishing to see him. But it went through her like a flash of hot fire when, in passing, he lurched against the dresser, setting the tins rattling, and clutched at the white pot knobs for support.

He hung up his hat and coat, then returned, stood glowering from a distance at her, as she sat bowed over the child.

“Is there nothing to eat in the house?” he asked, insolently, as if to a servant. In certain stages of his intoxication he affected the clipped, mincing speech of the towns. Mrs. Morel hated him most in this condition.

“You know what there is in the house,” she said, so coldly, it sounded impersonal.

He stood and glared at her without moving a muscle.

“I asked a civil question, and I expect a civil answer,” he said affectedly.

“And you got it,” she said, still ignoring him.

Again, it’s a novel with flaws: the build-up of the relationship between Paul and Miriam could be cut in half I think (again, where are you strong editor?). There are longueurs here because we have already grasped what is going on – the same themes are played out too many times for the reader. It also goes too far away from Paul and his mother, which seems central. So, not perfect, but still a very good novel in my opinion.

Tedious

I know there are plenty of people who find Lawrence tedious and unreadable. And fair enough, if you find Lawrence tedious and unreadable that’s fine – we are all different. But my suspicion is that many people are shown the wrong books, especially The Rainbow – or don’t read the best books, like Lady Chatterley. Perhaps, with his poetry, he has been luckier – but also here, I suspect many people don’t look, since they expect to find some crude exaltation of the phallus. Many of his poems are about places, people, animals, flowers, landscapes and yes, relationships – but I can’t remember, off the top of my head, an entry on the phallus.

Anyway, to me, he’s worth reading – for pleasure, for excitement, for his unique take on things, whether you agree with him or not. As a young man I was completely thrilled by him. He was my hero, incredibly alive and vivid. I have read of quite a few other people who had similar experiences, especially when young.

I’d wondered if that would fade away if I read him again, as a much older man. And yes, I have more detachment when assessing his writing – for example, my view that a stronger editor could have made his novels even better. But overall, I am not disenchanted after reading much of his work again. I have an even keener appreciation of his descriptive powers – there are so many magical passages. And re his ideas, I’m perhaps more quietly reflective about them, seeing where I disagree with him, but still allowing he had much to say that really affects me, while also wondering at his extraordinary powers of intuition, about what moves, shapes and drives people from moment to moment, and even the same for animals.

George Orwell, author of “Shooting an Elephant,” who’d also fought in the Spanish Civil War and certainly knew about firing guns, wrote about a passage where Lawrence describes firing a gun at an animal and how you feel as you do it. Orwell mentions that Lawrence had almost certainly never fired a gun (there is no record of it) but said his description of what went through the shooter was exactly right. Lawrence had that ability. That’s a remarkable aspect of his writing.

Conclusions

Lawrence’s was a time when the unconscious was king. Freud was in vogue and Lawrence was interested in his theories, and produced his own. This naturally fueled his emphasis on the unconscious processes that impel human beings. I don’t disagree that there are unconscious processes, but quite a lot of that has been domesticated by science in our day. We have unconscious genetic drives, many (though not all) developed as an adaptation through evolution. That accounts for a large part of our unconscious.

Nevertheless, I have some intuitive sympathy for his view. I think the modern-day personal development movement is, at least in part, an effort by overly-conscious human beings, living in highly industrialized and technologized societies, to get in touch with their own bodies, to get out of their heads, to not think through everything, to be more aligned with the less conscious parts of ourselves – and that’s a healthy aim overall. I think Lawrence might have mocked some aspects of new-age spirituality, as more of the same old, same old – a new iteration of Christianity with all its faults. But I think he would have recognized that there was a common effort in much of this work, in line with his own beliefs. We are less aware of our bodies, less aware of the natural physical world, on the whole, and we do have a yearning to be more deeply in touch with those things and other people.

On the other hand, I disagree pretty profoundly that we should shelve our pre-frontal cortex, which is effectively what Lawrence argued at times. We still need more rationality, more science, more conscious regulation than we have – especially in the public and political sphere. If Lawrence had been a politician – and he wasn’t since he wasn’t fundamentally interested in politics – he would have been an absolute disaster. Some of his ideas, as articulated to Russell, would indeed have led straight to Auschwitz.

This isn’t to excuse him, but proto-fascist ideas about strong leaders needing to rule over the brute masses were very much in the zeitgeist unfortunately – and Lawrence sucked some of this in. He never saw the full horrors of these ideas, since he died in 1930, but it remains a stain on his life.

But with Lawrence, you don’t quite think he really believed in such stuff. Overall, I think he was too sympathetic and too intuitive to ever sincerely want domination by some humans over others. And he was too intelligent to actually conclude, in his serious moments, that we should dump our pre-frontal cortex and our rationality. After all he used both of those things copiously in his writing.

One of his last essays sums up some of these contradictions. He criticises people who “insist on loving humanity” claiming that this actually leads to hating everyone (as he said about Russell). There’s a grain of truth in there – there can be a kind of imposition of a false ideal that hides the real emotional beings we are underneath. There can certainly be a lack of real human-to-human feeling in it – these proclamations of universal love can be false, forced, ostentatious piety and so on. Maybe they even stoke or come out of hatred sometimes.

But then he also talks in the same essay, movingly for me, about a more real kind of “love of humanity”:

…still, away in some depth of us, we know that we are connected vitally, if remotely, with these colliers or cotton workers, we dimly realise that mankind is one, almost one flesh. It is an abstraction, but it is also a physical fact. In some way or other, the cotton workers of Carolina, or the rice-growers of China are connected with me and, to a faint yet real degree, part of me. The vibration of life which they give off reaches me, touches me, and affects me all unknown to me. For we are all more or less connected, all more or less in touch: all humanity. That is, until we have killed the sensitive responses in ourselves,

which happens today only too often.

So he admits a different kind of commonality and love, in and for everyone. This is very far from his fascist posturing from years earlier. And then, we have this:

Try to force yourself to love somebody and you are bound to end by detesting that same somebody. The only thing to do is to have the feelings you’ve really got, and not make up any of them. And that is the only way to leave the other person free. If you feel like murdering your husband, then don’t say: “Oh, but I love him dearly I’m devoted to him.” That is not only bullying yourself, but bullying him. He doesn’t want to be forced, even by love. Just say to yourself: “I could murder him, and that’s a fact. But I suppose I’d better not.”—And then your feelings will get their own balance.

So at the end, shyly and a little grudgingly, the pre-frontal cortex and its conscience and responsibility are let back in: But I suppose I’d better not. I think Lawrence’s writing – certainly his best writing – represents this kind of marriage, if you like, between fully and vividly expressed emotion, and the currents of the unconscious on the one side, and then rational, sensitive thought on the other.

Afterthought

Lawrence wasn’t alway solemn. He could be very funny. I was just re-reading this poem.

Canvassing for the election

—Excuse me, but are you a superior person?

—I beg your pardon?

—Oh, I’m sure you’ll understand. We’re making a census of all the really patriotic people—the right sort of people, you know—of course you understand what

I mean—so would you mind giving me your word?—and signing here, please—that you are a superior person—that’s all we need to know—

—Really, I don’t know what you take me for!

—Yes, I know! It’s too bad! Of course it’s perfectly superfluous to ask, but the League insists. Thank you so much! No, sign here, please, and there I countersign. That’s right! Yes, that’s all!—I declare I am a superior person—. Yes, exactly! and here I countersign your declaration. It’s so simple, and really,

it’s all we need to know about anybody. And do you know, I’ve never been denied a signature!

We English are a solid people, after all. This proves it. Quite! Thank you so much! We’re getting on simply splendidly—and it is a comfort, isn’t it?—

Leave a comment