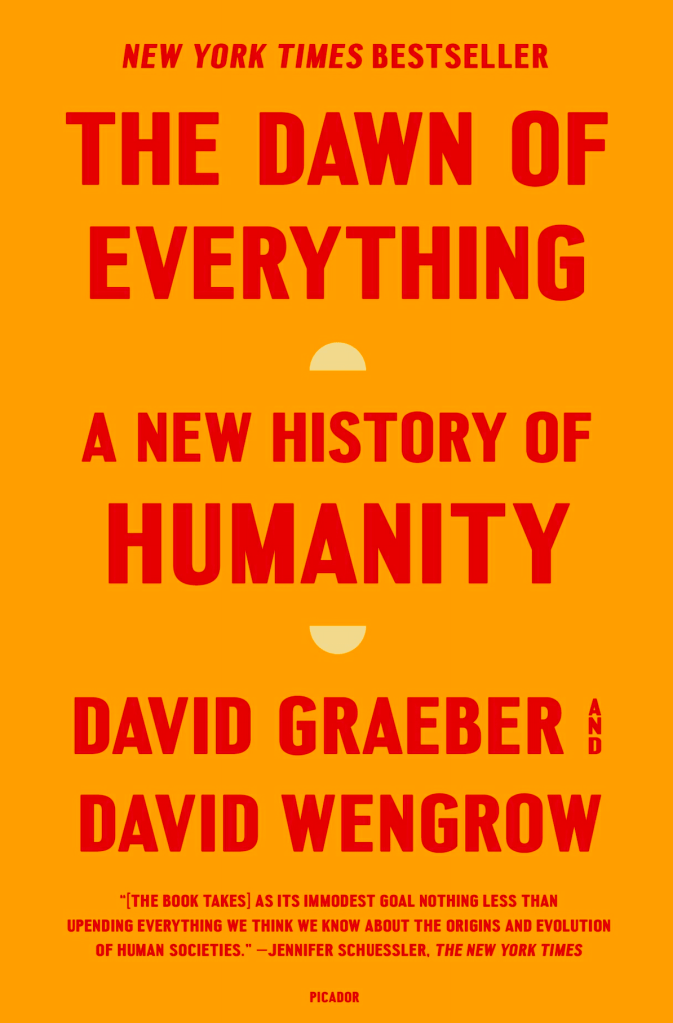

First the positives: I found this book informative and interesting on several levels – not having read a whole lot of anthropology. The essential message I took away was that human development and the way we organize our societies, is a complex process and the simple narrative of – small hunting bands led to organized agriculture led to top-down dominating states – is far too simplistic and is contradicted by large amounts of evidence

For example, each of these forms of society above had multiple, different characteristics in real life – some equal, some unequal, some violent, some less violent, some hierarchical and some non-hierarchical – and these tendencies existed alongside each other, and in different formats, during the same periods of human history.

David Graeber argues there is no natural and inevitable progression from one system, and one tendency, to the other. Essentially, the writer argues, any system of organization in society is not deterministic – not determined by technology, nor by the size and complexity of the social group. Instead, he says, these characteristics of society are fundamentally up to us. We can always change our society, using our own brains and imagination.

All this is welcome. I find it persuasive.

However, a major part of the book is unpersuasive to me. Graeber clearly indicates his view that modern society is based fundamentally on domination and is unfree – people are “stuck” or trapped in this modern unfree society and history has taken a very wrong turn.

Graeber: If something did go terribly wrong in human history – and given the current state of the world, it’s hard to deny something did – then perhaps it began to go wrong precisely when people started losing that freedom to imagine and enact other forms of social existence, to such a degree that some now feel this particular type of freedom hardly even existed, or was barely exercised, for the greater part of human history.

The problem is that Graeber changes his methods. In his accounts of past developments in societies, he uses copious examples to bolster his argument. But when it comes to the contemporary situation, he offers pretty much no evidence to support his statements. All we have are repeated assertions. He abandons complexity. I fully expected the last chapters of the book to factually support his contention that modern societies are unfree and more hierarchical than at any time in human history. But there is no factual support, at all, which I find astonishing.

To say the least, modern societies are highly complex and varied: they contain national and local political systems; multinational corporations, cooperative groups, communal living arrangements and businesses: households and civil society groups, neighbourhood councils; church communities and international organizations aimed at fostering global cooperation and justice. There are systems which demonstrate naked capitalism, but also authoritarian communism, advanced social democratic societies with well-developed welfare systems and universal access to healthcare and education, and war-torn dictatorships with no support for the poor. We see peaceful middle-income countries, sometimes without a standing army, and violent developing and rich countries. We live in pleasant, law-abiding cities and violently disrupted villages. All with varying degrees of democracy and hierarchy. And so on.

The authors clearly believe, from a few throw-away remarks, that modern democracy is a sham – that it is merely a continuation of show contests between charismatic individuals – and that we all live in fundamentally hierarchical systems. But again, no evidence is brought to bear to make this assertion. Instead, we are left with the broadest possible generalizations about society, not backed up with any surveys – at all. Again, absolutely astonishing. Historical analysis ends at pre-industrial times, and afterwards, we simply have sweeping personal opinion. How are we supposed to find this persuasive?

Graeber: As we’ve said before, there are certain freedoms – to move, to disobey, to rearrange social ties – that tend to be taken for granted by anyone who has not been specifically trained into obedience (as anyone reading this book, for instance, is likely to have been). ..It’s clear that something about human societies really has changed here, and quite profoundly. The three basic freedoms have gradually receded, to the point where a majority of people living today can barely comprehend what it might be like to live in a social order based on them. How did it happen?…

If there is a riddle here it’s this: why, after millennia of constructing and disassembling forms of hierarchy, did Homo sapiens – supposedly the wisest of apes – allow permanent and intractable systems of inequality to take root?

Apparently, we are so brainwashed by contemporary conditioning and propaganda, that now, for the first time in history, we are incapable of thinking through our societal arrangements or changing anything. A rather obvious point is that this book is itself a counter-example to this. But apparently, society is so monolithic that the vast majority of humankind is no longer able to think critically or challenge orthodoxy. Contemplating the reems of philosophy, commentary, history and analysis that is published and available on the internet, with often wildly different perspectives and proposals, does Graeber really think this is the case?

Of course, there are also substantive differences to mention. I don’t personally believe that modern democracy is a sham. Many analysts argue that democracy makes a large difference to people’s lives – the statistics show that democracies are less likely to massacre their own populations, less likely to go to war, and, as per Amartya Sen’s work, less likely to see famines – just to mention a few aspects.

The authors imply that the current system of democracies is falling apart. I would agree that the last decade has shown some regression on this front – but if you are looking at the longer term, the advancement of democracy has been quite extraordinary and rapid. Modern democracies didn’t emerge until roughly the end of the 19th century and the beginning of the 20th – but nowadays, the various organizations that assess democracy globally (eg Freedom House, VDem, Harvard’s Polity project, The Economist’s Democracy Index etc) generally say about 80 -90 countries are democracies – almost half of all nations. That is truly extraordinary progress. In the mid 1970s only about 35 countries were considered democracies.

These developments have been accompanied by vast strides in global health and in other areas – the incredible impact of immunization, for example, which, in the WHO’s estimate, saves 4 – 5 million lives a year; we currently have the lowest proportion of people living in poverty in world history, the highest level of access to education in world history; and, taking the longer view, the lowest proportion of the global population dying violently in human history, and so on.

I was ready and interested to hear an account of why and how the authors consider that the world has taken a very wrong turn – but it is simply absent from this book.

Steven Pinker has written about many of these issues – and, unsurprisingly, he is a target of criticism by the authors, since his conclusions about modern society are very different. The criticism of Pinker in the book is pretty vicious and almost entirely unrepresentative of what he actually says.

Graeber: Pinker argues that today we live in a world which is, overall, far less violent and cruel than anything our ancestors had ever experienced. Now, this may seem counter-intuitive to anyone who spends much time watching the news, let alone who knows much about the history of the twentieth century. Pinker, though, is confident that an objective statistical analysis, shorn of sentiment, will show us to be living in an age of unprecedented peace and security. And this, he suggests, is the logical outcome of living in sovereign states, each with a monopoly over the legitimate use of violence within its borders, as opposed to the ‘anarchic societies’ (as he calls them) of our deep evolutionary past, where life for most people was, indeed, typically ‘nasty, brutish, and short’.”

This is a simplistic reduction of Pinker’s arguments. Yes, he argues that the development of the governing state was a significant stage in reducing overall levels of violence – but he does not argue that this is the ONLY factor. For example, he posits that an enormous number of other factors – from the printing press, the dispersal of ideas and knowledge of other peoples, the development of the idea of human rights, increased trade, the growth of democracy, the establishment of international conventions and organizations to manage and resolve conflict; increased access to education and so on are also very important parts of the story – to name but a few.

This is followed by an even more ferocious attack:

Graeber:

For obvious reasons, Hobbes’s position tends to be favoured by those on the right of the political spectrum, and Rousseau’s by those leaning left. Pinker positions himself as a rational centrist, condemning what he considers to be the extremists on either side. But why then insist that all significant forms of human progress before the twentieth century can be attributed only to that one group of humans who used to refer to themselves as ‘the white race’ (and now, generally, call themselves by its more accepted synonym, ‘Western civilization’)?…Insisting, to the contrary, that all good things come only from Europe ensures one’s work can be read as a retroactive apology for genocide, since (apparently, for Pinker) the enslavement, rape, mass murder and destruction of whole civilizations – visited on the rest of the world by European powers – is just another example of humans comporting themselves as they always had; it was in no sense unusual.

Pinker would indeed be monstrous if he says any such thing, but if you actually read his books, you know that he doesn’t. Firstly, he never argues that human progress was exclusively a Western thing or by the white race. Two examples from Enlightenment Now, the first a section from some background he provides on the development of Enlightenment ideas:

Around 500 BCE, in what the philosopher Karl Jaspers called the Axial Age, several widely separated cultures pivoted from systems of ritual and sacrifice that merely warded off misfortune to systems of philosophical and religious belief that promoted selflessness and promised spiritual transcendence. Taoism and Confucianism in China, Hinduism, Buddhism, and Jainism in India, Zoroastrianism in Persia, Second Temple Judaism in Judea, and classical Greek philosophy and drama emerged within a few centuries of one another. (Confucius, Buddha, Pythagoras, Aeschylus, and the last of the Hebrew prophets walked the earth at the same time.)

And then here:

a common criticism of the Enlightenment project—that it is a Western invention, unsuited to the world in all its diversity—is doubly wrongheaded. For one thing, all ideas have to come from somewhere, and their birthplace has no bearing on their merit. Though many Enlightenment ideas were articulated in their clearest and most influential form in 18th-century Europe and America, they are rooted in reason and human nature, so any reasoning human can engage with them. That’s why Enlightenment ideals have been articulated in non-Western civilizations at many times in history. But my main reaction to the claim that the Enlightenment is the guiding ideal of the West is: If only! The Enlightenment was swiftly followed by a counter-Enlightenment, and the West has been divided ever since. No sooner did people step into the light than they were advised that darkness wasn’t so bad after all, that they should stop daring to understand so much, that dogmas and formulas deserved another chance, and that human nature’s destiny was not progress but decline.

I do find Graeber’s chapters about how Native American indigenous thinkers may well have influenced Enlightenment thought interesting and informative, but as above, Pinker is very much open to considering non-Western influences and ideas.

Secondly, Graeber’s assertion that murder, rape and genocide were things that, according to Graeber, Pinker believes are just another example of humans comporting themselves as they always had is entirely false if you read Pinker’s books, like the Blank Slate and others.

Pinker’s main point in these books is to re-introduce consideration of genes into the debate about society and human behaviour – which he argues, putting it briefly and crudely – has been excluded from accounts, especially on the left, because of the association of genetic research with eugenics in the 20th century. Pinker argues that we have a range of impulses – from violence, fight and flight – to nurturing and cooperation. He never, ever says that violence is the dominant driving force, or that humans “always” tend to comport themselves violently. Quite the contrary, of course, since he devoted two whole books to explaining why human behaviour has become less violent.

Graeber then goes on to accuse Pinker of cherry picking. This is pretty rich, since Graeber’s book is entirely based on selected narratives about historical groups and societies. There is virtually no statistical analysis at all. Yes, Pinker also chooses to illustrate his arguments with selected accounts, but he also supports it with enormous quantities of statistical surveys and reports – no one could possibly accuse him of relying on anecdotes. This contrasts, ironically, with Graeber, though his anecdotes are indeed copious. Graeber deigns to address this issue thusly:

Graeber: Whatever the unpleasantness of the past, Pinker assures us, there is every reason to be optimistic, indeed happy, about the overall path our species has taken. True, he does concede there is scope for some serious tinkering in areas like poverty reduction, income inequality or indeed peace and security; but on balance – and relative to the number of people living on earth today – what we have now is a spectacular improvement on anything our species accomplished in its history so far (unless you’re Black, or live in Syria, for example). Modern life is, for Pinker, in almost every way superior to what came before; and here he does produce elaborate statistics which purport to show how every day in every way – health, security, education, comfort, and by almost any other conceivable parameter – everything is actually getting better and better. It’s hard to argue with the numbers, but as any statistician will tell you, statistics are only as good as the premises on which they are based. Has ‘Western civilization’ really made life better for everyone?

Well, it is hard to argue with numbers as he says, but it seems rather churlish given that Graeber does not provide statistical analysis, to simply question Pinker’s statistics and make no attempt to counter them with figures of his own. The statistics are easily available – the UN collects them globally – and, as stated above, on most measures, human beings overall are happier, less poor, healthier and better educated than at any time in human history. Nobody in this field, including Pinker, says that poverty and inequality don’t still exist and that the world must not do everything it can to reduce these blights. It’s quite absurd to accuse Pinker of neglecting this – did Graeber actually read Pinker’s books?

Secondly, Pinker goes to great lengths to explain that he is not an optimist. He argues frequently that progress is not inevitable and that the world can easily backslide. What he does argue is that, according to the measurements taken as above, we should look at this and see if there are lessons to be learned about what worked and didn’t work in making those improvements. Claiming that nothing has worked is false – according to the statistics – and claiming that everything is worse now than ever before, is not only wrong, but can lead to a fatalism which will mean we won’t learn from the lessons of history.

Of course, at the heart of this argument, is a basic feeling and perspective about the current world. Graeber’s view is clearly very negative and pessimistic. I don’t have those thoughts and feelings – and I argue that the statistics and evidence support a more positive stance.

I do however appreciate the large amount of historical and anthropological insight in this book, and welcome its embrace of the complexity of different forms of societal organization through much of human history. Where I differ most profoundly with Graeber is that I believe this complexity persists to this day, and didn’t disappear with the industrial revolution.

Leave a comment