Note – this was addressed to my colleagues at the UN’s Video Section on my retirement, in 2023.

Dear all

I wanted to share a few thoughts after 25 years working with the UN family – 8 with UNICEF, a couple of years with UN News and OCHA – and then about 15 with UN Video in various formats. Before that I worked for 11 years as a reporter and producer for the BBC.

Main point: I’ve had a fantastic time. When I decided to switch from the BBC a colleague said, “you won’t fit in at the UN. It isn’t you.” That worried me a bit, but I felt that I needed a change. I’d got fed up with being on the same treadmill – current affairs, or whatever programme I was working on. I wanted to do something different. And besides, the UN was based in New York, which I’d first visited, not long before, and loved. A BBC colleague had been giving some training at UNHQ, and she advised me to try. I got a gig giving trainings to UN Radio initially, then got another gig at UNICEF and – I’m still here.

Me with cameraman Khalid, on a filming trip to Gaza.

Does this job matter?

As you may well have seen, I’m a fervent advocate that the UN, along with many other things, has made a significant, substantial, positive difference to millions upon millions of people. Yes, it can be frustrating. Yes, the hierarchy and bureaucracy can be maddening – and yes, there are many failures – but there are plenty of hard facts about human progress to think about:

- highest proportion ever of global population accessing education and healthcare

- lowest proportion of people ever living in poverty

- vastly increased literacy

- lowest levels of violence in history (taking the long-term view)

- global population increase slowing significantly and the highest longevity in history

- lowest proportion of people dying from preventable diseases

- historically, a very high number of democracies in existence today (roughly half of all countries – which, given that the first modern democracies only appeared not much more than a hundred years ago, is formidable progress)

(Yes, the last ten years has seen a negative uptick on some of these trends, but if you look from a perspective of 3,000 years, 1,000 years, 500 years, 100 years or 50 years – all the trends above are definitely and significantly positive).

Multiple factors are at play here –

- scientific and technological progress and increased know-how – especially improving our health (vaccines alone save up to five million lives a year, according to WHO)

- more effective governments – limiting violence and also able to provide infrastructure – roads, schools, houses, hospitals

- Increased trade and international interaction

- Vastly different attitudes to war – no longer seen (mostly) as something prestigious – not the case a hundred years ago (See Richard Ned Lebow, Why Nations Fight and Steven Pinker Our Better Angels) leading to far lower levels of violence, far fewer wars, far fewer combat deaths as a proportion of the global population (again taking the long view)

- increased global economic prosperity

- the establishment of the idea of human rights, especially from the Enlightenment onwards, and through the Universal Declaration of Human Rights of 1948, the Geneva Conventions and so on

- increased knowledge about other people on the planet, opening up greater possibilities of mutual empathy and understanding

- increased international diplomacy, mediation and peacebuilding

- vastly increased international cooperation – through regional bodies like the EU and the African Union, and global bodies like the UN

The UN is part of this process – a significant part – pushing for greater cooperation, pushing human rights, supporting development, constantly mediating conflicts, and peacebuilding, deploying peacekeepers, whose presence, contrary to what you might read in Western media, has literally saved millions of lives, ended conflicts, allowed the conditions for peace agreements that stick, significantly cut civilian casualties, and reduced the outbreak of renewed hostilities by 80%. (See Prof. Lise Howard, Power in Peacekeeping, Georgetown University, which is based on her own research as well as 16 peer-reviewed studies.)

Yes, there’s still inequality, poverty, conflict and we have the huge, global challenge of climate change, but I believe the UN points us in the right direction: let’s continue to tackle all of these, working together.

It’s also true that some of the progress we see only comes very slowly – inching forwards, year after year. And there are often setbacks. But new conventions, laws, norms, collaborative efforts and behaviours make a difference, in the long run – we can see this reflected in the hard statistics that we gather.

So we are working for an organization that matters. For me it’s been an incredible privilege – using my creative abilities for a good cause, travelling around the world, filming interesting things and interesting people and being paid for it – on a salary.

I think Chaim Litewski, our former chief, said once that the P3 videographer post was the best job in the UN system. I’m inclined to agree with him (well maybe SG and some other posts). Your tasks are mainly creative – producing films – and because you are not seen as too significant a player on the food chain, you don’t have to go to too many meetings!

My colleague at the BBC was wrong: I had an incredibly lucky break and made the right decision.

At UN Video we can contribute to a dialogue about a better way: through increased understanding of each other, through showing human courage and human dynamism to change things for the better; human resilience against great hardship and cruelty; human determination to right wrongs, bring justice and restore stability; human joy, love and caring; human capacity to build societies that serve us in enduring ways.

And one of the most powerful ways to influence people in this dialogue is to move them with storytelling.

That matters. Our job matters. So keep on keeping on.

What works from my perspective – re UN Video

This tract was originally going to be based on notes for a potential workshop on video storytelling, over a year ago. Alas, I was too sick to run the workshop, and then we hired Annalise (to work with us, partly on storytelling approaches for YouTube) so it became somewhat moot. Also, of course, Al Tompkins has frequently added in his invaluable insights – and then we’ve had some good discussions on Solutions Journalism and so on.

So most of the ideas below are filling in gaps – things I have thought about, but which weren’t completely covered by the above people. Much of this relates to my own experience of making videos for the UN. I might also digress a tad here and there, commenting on things I like on the general film scene at the moment. So not comprehensive, but hopefully interesting – and of course you are free to disagree and blow raspberries at anything I say.

So – video storytelling – these are some categories that occur to me as important:

Casting

My friend Antonio Tibaldi, who’s a distinguished feature film director, and has filmed on numerous UN Video trips, runs a directing class at City College. I’ve sat in on his course a couple of times. His main workshop element is to have each student rehearse a scene with actors in front of the group – who then give feedback. A really interesting exercise. I made a short drama myself after taking part.

Anyway, I always remember Antonio saying this: “Directing is 90% about casting – it’s getting the right actors for the parts. You can tweak things a little with directing – but you can’t make a fundamental difference.”

I think that definitely applies to non-fiction documentaries. It’s all about who you select to film. Our style of character-driven videos depends very, very much on the people we find to film. The story hangs on them – can they convey emotion? Is their personal story gripping? Do their personal actions tell a story and draw in a viewer? Are they good speakers, can they articulate what they are experiencing? Or can they convey that in other ways?

When I was at UNICEF, I remember we had some meetings with a Dutch filmmaker, Duco Tellegen. He’d made a series of gripping films about young people – one of which was about a Lord’s Resistance Army member, who wanted to return to his community. The key moment was when he met with his mother and asked to be let back into his home and village. He had committed atrocities in his own community, so it was an especially difficult and sensitive conversation. The filmmaker had managed to film this precise moment.

Two things – a) he told me that he interviewed sometimes as many as 300 people before selecting his main subjects (OK that’s not realistic for most of our projects, but the basic idea is there – patiently wait, focus on selecting the right person as far as you possibly can).

The second thing he told me was also very interesting, I thought. He told me that effective films bring out internal processes in people – their internal emotions, thoughts, reactions – yes, as conveyed externally and visually. But he argues that what really strikes home and connects is seeing a person processing an emotion.

Through this experience, the viewer can identify, sympathise, empathise, sometimes root for the character – or at least be very interested in what this character is doing and what the character will do next. The director told me it was relatively easy to create external scenes – fast-moving camera, quick editing to convey action – but that wasn’t as powerful, didn’t get to the heart, as much as a scene where an internal emotional process is taking place.

Another of his films, again after very extensive casting efforts, was a film about a mother telling her young son that he had HIV, passed to him by his parents. He captured the very moment that she broke it to him, watching both her feelings as she conveyed this and the reaction of the boy. Again, not highly dramatic external action, but the emotion of the exchange.

Since it’s me, I’ll give a couple of links to videos I’ve done where I hope the casting worked pretty well.

The first is, My Dreams are Huge, which is a profile of two people with disability in South Africa. The first character is Eddie NDopu. He has now, to my great unsurprise, become a UN spokesperson on disability rights. He is an incredibly articulate and forceful speaker. And here, Thank God for YouTube. I cast him after trawling around on the internet, and found a couple of short videos in which he spoke. At that time, he had no connection with the UN. I was instantly converted and knew he would be great. The second character I got through careful discussions with an NGO in one of the townships: Ntswaki Tsoliwe. She has a strong story, has an emotional presence and is a powerful character.

This is the video:

And then, secondly, is this video about survivors of terrorism in Norway. There was a very powerful story already built in: the massacre of 69 youth on a small island in a fjord in Norway, all shot to death by a lone and heavily armed gunman. The Office of Counter terrorism wanted a film that focused on survivors/victims. (To note: “victim” was the officially terminology of the UN unit that was supporting this.)

Again, I knew from reading and watching, that both characters I selected would be strong. On paper, they had powerful stories – Kamzy Gunaratnam had swum away from the island, even though she was barely a swimmer, and had now risen to the position of deputy mayor in Oslo. Viljar Hanssen survived an almost unthinkable ordeal.

Again, I did show some external action – a recreation of running away from the shooter, for example – but I hope the video shows some of the internal emotional process as well: Kamzy taken back to the place where she swam to safety, Viljar reflecting on the terrible injuries that were inflicted on him, and how he has slowly managed to recover. To repeat, I do mix this with some external activities – I’m not arguing for eliminating external action – but I am arguing for creating the conditions in which the internal emotion can come out and be felt.

In addition to the basic casting, of course, is doing everything you can to establish rapport, comfort and ease with the characters. If at all possible, I always try to hang out with my film subjects as long as possible – and I never interview them in depth on camera, if I can help it, until I’ve spent some time with them, so that they get used to me and being on camera. I tend to be “real’ with them – owning up to my thoughts and emotions, sharing anything that I’ve experienced that might be relevant, and open to having real discussions. Sometimes, I’ve remained friends with the people I’ve filmed, which is always the best outcome.

Also, it is not necessarily bad for people to talk about terrible things they have experienced. Of course, this requires good judgement and a great deal of sensitivity. For some people, it is evidently retraumatizing to share their experience – in fact, one potential interviewee in Norway conveyed this to me, and of course I’m glad she did. But others are sometimes willing to share for a constructive cause because they think there are important things that they want to convey which would be good for other people to know. For yet others, it’s actually therapeutic to talk about their experiences – they want to talk about them and welcome the opportunity. And every variation in between. I guess what I’m saying is, it’s not necessarily wrong to invite people (in the right circumstances) to talk about very bad things – there are times when it’s a mutually good thing to do. And there are other times when it could be very wrong and destructive.

Here’s the Norway film:

And here’s another short film – a very simple format – an interview with UN staffer Ken Payumo who helped prevent 80 armed men entering a UN compound in South Sudan, where thousands of civilians were sheltering. Again, I hope Ken’s internal emotion comes across – especially as he recounts making a decision that might have cost him his life:

The journalistic/reporting view

This was something close to the heart of UN Video’s former chief Susan Farkas. It’s close to my heart too. She felt that, at least for our longer, in-depth, pieces we should make them as close to say, a BBC, or NBC production as possible. When I worked for the BBC, it was required to make strenuous efforts to get a rounded view of any story – a view that brings in competing, different, or opposing perspectives.

Yes, there’s a caveat here: we are not doing pure journalism exactly as if we were working for the BBC. For one, we have limitations on what we can cover. We can’t cover, say, the political aspects of Tibet, for instance, unless there’s (a pretty unlikely) specific statement by our human rights office. So we can’t just choose any subject we want and include multiple perspectives on that subject. That’s a fact of life that I regret, but I think on balance our work is still valuable.

What we are doing is somewhat different – it’spromoting an agenda, essentially promoting a more collaborative and cooperative approach to human rights, development, and peace and security. We are not for example promoting the idea that nation states should act primarily only in their own interest. We are arguing that a global, cooperative approach – say to climate change, poverty and international peace – is more likely to succeed. We have a position on fundamental things – we are, of course, for human rights.

I am essentially OK with that adaptation from pure journalism since I support the UN’s broad agenda. It’s worth supporting. But within that agenda, I still think we have enough room to apply a journalistic approach to our stories, as far as feasible in each case. We should, I believe, seek to have a rounded, pluralistic perspective on issues, or events, where possible.

Again, I’ll offer up another piece I did, this time in Detroit. The subject was the decision by the city authorities there to shut off water supply to people who weren’t paying their bills. Two UN Special Rapporteurs were visiting Detroit so it seemed a perfect opportunity to report on this issue. In essence, the piece was about poverty – a family struggling to make ends meet, but who had also been affected by the water shut-offs.

The UN’s perspective is that access to water is a human right, and any policy of shutting off water should not be allowed. But why was the city council shutting off the water? That for me was definitely worth exploring to fill out the story. The answer was that there had been massive depopulation of the city, and therefore the city was struggling to maintain the water system: it was designed to cater to, and be funded by, a considerably larger number of people. The city also said they had set up a fund for people in difficulty with their water bills.

I added in this perspective, but also looked into that further: the fund wasn’t reaching many people who’d lost water, the rules around it were prohibitive, and the fund probably wasn’t big enough anyway. I used snippets of statements by the mayor and other water officials giving their side. I also sought an interview with a city official – which was denied. But I was nevertheless able to bring different perspectives, which, I hope, make the piece more interesting:

An afterthought: if I’m watching a broadcaster cover an issue, I definitely want to see people expressing views different from my own. I want to know why people think differently from me, and what they are actually thinking. If I don’t hear opinions different from my own, I’m not satisfied – and, in fact, I’m less trusting of the broadcaster.

Boundaries

To what extent can we push boundaries – what if the government doesn’t agree with what we put in a piece? I believe, from experience, that there is room for us to push boundaries.

One example from my work: a piece on the Saudi programme to rehabilitate men who’d joined terror groups (there’s currently a huge outcry about another filmmaker who recently made a piece at the same Saudi centre – which raises a lot of interesting issues, too lengthy to go into here).

A UN colleague in Saudi told me he felt our role was to push countries on human rights. This influenced me. The piece I eventually made included an interview with Human Rights Watch, which criticized the Saudi justice system. I reported on some of the failures of the “rehab” programme, underlined that Saudi Arabia had a problem with men joining terror groups, and reported that only a minority of prisoners were placed in the programme.

At the same time, I believed a story about how people leave terror groups, and how they could then could be rehabilitated into society, was a little-covered subject at the time (2011) that was definitely in the public interest to report on. The piece mainly focused on a Saudi citizen, formerly a bomb-designer for Al Qaeda, who’d met Bin Laden, who’d been through Guantanamo and the rehab centre, and was now settled back into Saudi society, married and with a job. It went out on 21st Century.

Another time, I made a film in Azerbaijan focused on human rights. The government was demolishing a whole area of the city to make a public park. As far as I could find out, little consultation was taking place, and residents were sometimes being forcibly removed from their houses – in fact, I’d found video of a brutal eviction taking place. I tracked down the woman who’d filmed people smashing their way into her apartment, and she became the lead character in the piece. I did submit a request for an interview with the authorities, which wasn’t answered, but mentioned the government’s public line about the park. Stéphane Dujarric, at time the chief of News and Media Division, agreed we could put the piece out.

Working with the UN and editorial control

One of the repeated lessons of working in the UN system, is that when part of the UN asks for a video to be made, you should take a really proactive role in defining what the film is going to be about, who it is aimed at, and how it is to be done. Remember that you almost certainly know more about videos and distribution than your client.

OK – a bit of a vent here – audience warning.

The stark truth is that many people working within the UN system are, I’m afraid, not smart about video and also not capable of communicating effectively outside the UN. In fact, it’s often worse than that. Sometimes, making an interesting or effective piece is not even on the agenda. What is on the agenda is pleasing a person in a superior position in the UN system. This has been the case in various cases I have encountered: no one in the commissioning unit or agency actually cares if the video is good in any meaningful way, so long as the boss, or the big boss is happy.

So your task is to persuade your clients, in this instance, to think about engaging with an audience beyond the UN system. The challenge is enormous: you are asking members of the public, not connected with the UN, to spend some of their leisure time watching a video that is related to the UN – in the midst of cut-throat, highly motivated and professional competition from other social media, multimillion dollar movies and TV series.

One question to ask – (or at least imply) – is this: would you watch this video in your spare time? Come on, realistically, would you? If the honest answer is no, then you have to ask the hard question: is making the project worth it – or not? Making a product that no one, outside captive colleagues at the UN, is going to watch, is simply throwing money away. Nor is pleasing a bureaucrat in the UN building, to my mind, worth a major effort.

It’s the public outside the UN we should be aiming at: to move them, to influence them, to catch their attention. And in my (unoriginal) opinion, one of the very most powerful ways of influencing a human being is to tell them a compelling story. Every culture, throughout human history, has storytelling. So tell a story.

But sometimes, there’s no way out. I, for instance, got asked to make a video which included, I think, about 6 UN officials all making statements to camera. This is the other factor we are up against: videos are seen as a way to smooth over political problems by including EVERY official that might be involved. This is not a good idea. But anyway, I dutifully made the video– trying hard to distract viewers with visual displays, music and graphics (attempting to distract them from this essentially dull concept – more on this later) and it was screened at a conference.

But then, yet another problem. Video is often so little understood, and all too frequently, alas, so little valued, that they arranged for the video to be played exactly at the point when people were moving around the auditorium. So essentially, the organizers ensured that no one watched it anyway – even though they’d spent considerable time on it.

A common scenario.

And let me give some more opinions on the above. My view is this – you can fool some of the people for a short time, but you can’t fool any people for a long time.

In practice, I think you can sometimes get away with distracting people for up to a minute with a lot of bells and whistles – slick editing, cool graphics, nice fonts, dynamic music – but beyond that, if the basic material is uninteresting, that will show. In short, to use an unpleasant but memorable phrase, you can polish a turd, but the turd remains a turd.

And when I speak of “up to a minute” I’m mostly speaking about the short campaign video or conference opener – essentially a kind of advert, which is part of the output we are required to do at the UN.

To extend my argument further, and thinking especially of character-driven pieces: if you have a strong, emotional story, the camera and the camerawork can be average, and the graphics may not be stunning, but people will be absorbed, because they will be following the characters and will want to know what is going to happen to them. So long as they can see and hear the material clearly, they won’t notice the quality of the other elements, if they are deeply engaged in emotion.

In the reverse case – where you don’t have engaging material, but you have the best graphics and fonts in the world, excellent camera-work and slick editing – viewers will still not be engaged. They will be bored.

In essence, the stronger your material, the fewer bells and whistles are needed. I am not arguing that the other elements aren’t useful tools – they are, and they can contribute to making a good story even stronger, and we should strive to use them – but they aren’t the core of what we are looking for. They can’t transform dross into gold.

Some of this applies to explainers as well. When you have an on-screen person presenting the explainer, the person needs to be a good and engaging speaker, and to provide a clear and engaging narrative. Even with a non-hosted, purely textual explainer, the text needs to provide a clear, engaging narrative of information. It still mostly comes down to content.

Anyway – deep breath – and now proceed.

What story do you tell?

One problem, in the field, is that sometimes when you arrive at a UN-supported project, you discover that very little, or nothing is going on. Even worse, a colleague of mine reached a project and found that the main person, (who was receiving funds from the UN) was essentially a drunkard who slept all day, and did nothing.

That’s a tough one. In this instance, my colleague managed to film in the field on the issue at hand, without centrally involving this particular individual – so they were adaptable enough to find a way of covering the relevant subject matter. In these situations, we have to be very creative and resourceful – and the aim is still to find a story that is relevant and accurate.

I would never, ever advocate for a piece that essentially fabricates a narrative about a project that is, in fact, achieving nothing. Also, as Susan Farkas argued, and I strongly agree: if the UN has had failures in a particular area, we should report that – as well as showing what is being done to rectify that situation. A piece is far more credible (and persuasive) to an audience, especially when there’s scepticism in that audience, when faults and mistakes are acknowledged as part of the narrative.

But anyway, more often than not, a typical filming trip will involve going to see a UN project – that’s the way the funding works. But it’s good to think carefully about this. I don’t believe we should have the mindset that we are filming a “project”. I think the mindset should be – ‘what great story can I tell about people?’ and then attach the project to this. It should be ‘story with a project involved’, rather than ‘project with a story involved’, if that makes sense. (In Azerbaijan, I grafted a project about human rights promotion onto the central story about the housing evictions – I proceeded that way round.)

And on editorial control – I guess this is the way I was “brought up” – but at the BBC a cardinal principle was maintaining editorial control. It was up to the reporter and producer to decide on the editorial line of the piece. If the interviewees had agreed to participate, from then on, it was the BBC’s prerogative to decide how the material would be used and presented – yes, all the time being bound by principles of accuracy and also by a commitment to fairly representing differing views.

At UN Video we should also value this, I believe. We need to assert that it is our job to make the most effective video – we are the experts, and this is why we advise on doing it this way. Of course, we must allow checks for factual inaccuracies, but essentially, how we tell the story is definitely our business, and we should also make our case on which elements should be included (and, critically, excluded) in the video, in order to make the product more effective for outside public.

It’s sometimes easy to see only inside the UN bubble, but a good thing to remember is – what is the pre-existing climate of opinion outside in the world? (And this may and does of course vary from region to region). For example, is the default view of UN Peacekeeping a positive one? Or is it – ‘UN peacekeepers never do anything except abuse children?’ In some parts of the world, that is the view – and if we ignore that reality, we are not going to communicate effectively in that environment. This means acknowledging that climate in some way within a piece. So with peacekeeping, we need to acknowledge the well-known failures, whilst also pointing out that, if you look at the data, most of the time peacekeeping works.

Questions to ask yourself

Once, when I was about to leave for Iraq, where I made an independent documentary, I asked a bunch of friends what they would want to see in my documentary. I’m glad I did because one person said “hope” – and that was a really useful pointer, that guided a lot of what I did.

It’s kind of a naïve question, but I think it’s worth asking – you might be surprised into new and fruitful directions.

A couple more:

What is the key thing that you want to get across – and what will be the key moments and elements in the story that will do that?

Half-way through the project – is there something that could be better? Is there something missing?

And one more thought – reduce the description of your piece to a one-liner, with an active verb – it must be active. It’s a good discipline to do this – it will help develop a strong central, spine of the story and a clear direction.

For example:

A man stops armed troops entering a UN compound and saves hundreds of lives.

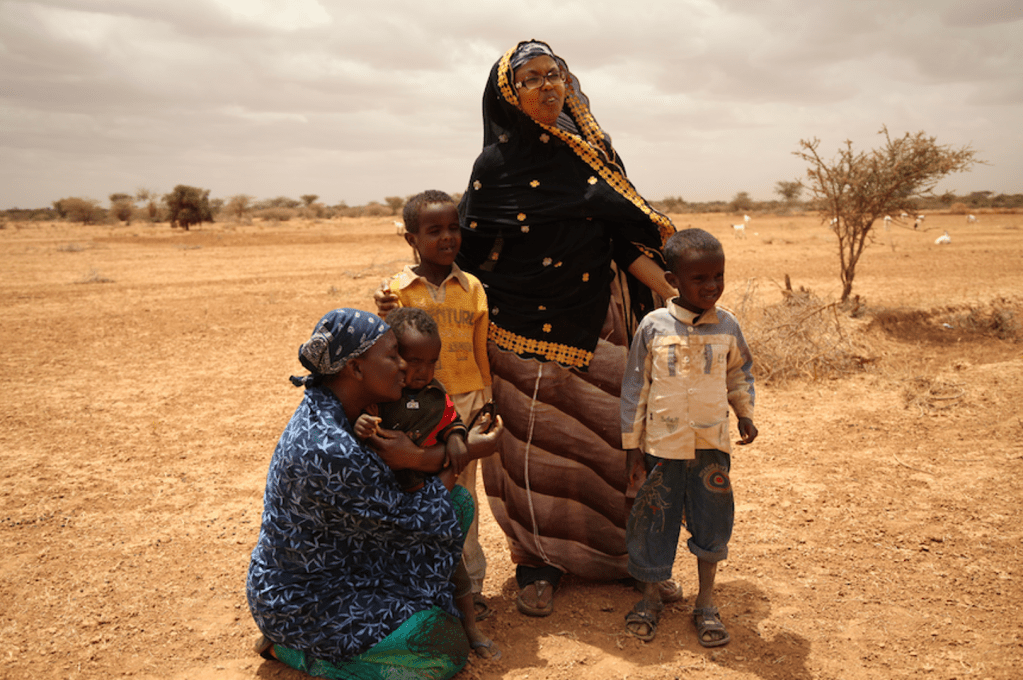

A woman helps goatherds stay in their village.

A farmer leaves his farm because of drought and embarks on a dangerous journey for salvation. (see link below).

More on projects:

Another example for me, speaking of projects, was filming in Somaliland. This was an NGO being financed partly by the UN Democracy Fund. The leader of the project, Amina Souleiman, was a highly capable, dynamic Somali woman who was working long-term in a village in rural Somaliland. This was an initiative that was visibly worthwhile and significant – a heart-reassuring example of the UN putting money to something that was really valuable.

Female goatherds were struggling to stay in the village since their goats were at risk of being decimated by drought. If the goat herd was destroyed, their livelihood was gone and they could be forced to move to the city to do barely-paid manual labour. We filmed in the village – picking out one of the women goatherds, and filmed in the city – an unfortunate older woman who had been forced to move to the capital, where she did back-breaking work for virtually no money.

The NGO worked to build up employment prospects in the village. They’d helped build a school, staffed by local women, and they encouraged the women to come up with their own ideas and work together, through ongoing discussions, workshops and cultural activities – and so on.

In truth, I’m not entirely satisfied with this particular video – we had some nice visuals, and some good moments, and we attempted to tell strong personal stories – but it remained a bit too much of a “project” video and not a human story first and foremost. We don’t always entirely achieve what we want, but we should at least know what we want and strive to get there.

Which brings me to another subject:

Safety and Security

If you are going to a potentially unsafe area, like Somalia, or Somaliland (Somaliland is a non-UN-recognized breakaway northern province) not only do you, of course, have to collaborate closely with the local UN offices and security people – but you should not go on your own. You are uniquely vulnerable when filming: firstly it draws attention, and secondly you can quickly get absorbed in your own bubble and not notice dangerous things developing around you.

I travelled to Somaliland with Antonio. His wife wasn’t particularly happy we were travelling there. We did get back safely, but we had a couple of scrapes.

Unbeknownst to us, rumours had been flying around the capital Hargeisa that Westerners were filming pornography in the city. It was a potentially volatile situation anyway. Onlookers were already not particularly happy that two, white Western men were filming women in the street. I was also harangued by someone passing in a car about how the UN was useless and was doing nothing in the country. So that wasn’t an especially good start.

But then things got worse. We were continuing to film our elderly lady – the unfortunate individual who had been forced to leave her home village. We needed to film her travelling back to the shanty town she was living in, which involved catching a bus in a crowded city square. Antonio and I had travelled to this spot with a driver and a UN vehicle, and the NGO were also on hand with their two vehicles.

As Antonio trained his camera on the woman next to the bus, shouting broke out. A large mosque was nearby and the area was really crowded. I now saw a young man running towards us. One of the NGO’s armed guards raised his rifle and the young man appeared to run into him, hitting his face on the rifle butt and falling to the ground. More shouting rose up. More young men swarmed forward. The NGO’s armed guards all raised their rifles – and for a moment I thought they might fire – which would have been a very bad thing all round. They didn’t fire, thank God.

Next moment, I bundled Antonio into the UN car and followed him in. As we did so, Amina, the NGO leader, was arguing, very courageously, with the group of men. Some of the young men now smashed the windows of the NGO vehicles. My driver said we should move – but I was frozen for a moment since I didn’t want to entirely abandon our NGO colleague. An armed NGO guard tried to get into our vehicle and I said no. There’s a principle that UN vehicles should not have armed people in them – for good reason. This could easily have attracted the mob to us and we needed, in this instance, to have the UN vehicle only for unarmed people.

Anyway, somehow Amina managed to calm the crowd down, and we were eventually able to move away.

That wasn’t the end of the story. Moral of the second part of the story: don’t send your UN driver and vehicle home when you are out in the field.

The next day, in the early evening, we were finishing an interview on the top of the NGO building and I glanced down into the street and saw a group of about ten armed men making their way in our direction. I wasn’t sure what it meant. But a few minutes later, a bearded man poked his head up out of the stairway and started an argument with Amina. She eventually followed him downstairs, and then I heard a general shouting match breaking out. I felt I needed to (literally) stand alongside Amina to give support, so I went down and did so. Several men were screaming at her. I of course didn’t know what was going on, but she was again arguing and explaining something. Then I realized some of the armed men had gone up to the roof, where Antonio had remained. When I got up there Antonio had been informed by Amina’s young daughter, who spoke English, that the men wanted to take us to the police station.

Unfortunately, for the one and only time on that mission, I’d sent our UN driver home, since I’d concluded we could travel back to our hotel in Amina’s vehicle. I didn’t like the prospect of going with these guys (who the hell were they anyway?) through the streets, so I came up with, what I think, wasn’t a bad idea. I sat down and encouraged Antonio to do so. The gesture wasn’t aggressive – but it also signaled we were not inclined to move. A good balance.

So for several more minutes, these (up to ten?) guys with rifles snarled and gestured at us, but I would simply gently shake my head every now and then. Very fortunately for us, they were not quite ready to drag us away physically, which they could have done. Meanwhile I managed to phone through to the Resident Coordinator, who informed our driver, and also phoned the local police commissioner, who he knew.

After a few more minutes, the men grudgingly asked for our IDs. We showed them, and they went away. I was somewhat surprised that the local UN allowed us to film the next day – but we were provided with armed guards and it went off without problems.

So don’t go alone. Don’t send your UN vehicle home. And always have a UN person’s number on our phone or radio.

Baghdad

There have been more lessons – not least being present when a suicide truck bomb blew up part of the UN’s Canal Hotel HQ in Baghdad – a story I’ve told elsewhere: https://news.un.org/en/audio/2018/08/1016932

Which brings me to another point: we don’t go on these journeys for the UN alone, in the literal and metaphorical sense. Our loved ones are also thinking about us. When the Canal Hotel bombing happened, my former partner Ariel was back in the US with her elderly mother, who was hard of hearing. Ariel tells the story of how she was setting up a DVD player and TV for her mother and flicked on the TV very briefly. She caught a few seconds from CNN, with an announcer saying, “And we’ll return to the UN Baghdad bombing in a few moments,” with footage of wounded people. Ariel clicked back to the TV and had to wait for the commercial break to end, while her mother didn’t fully understand what was happening.

One of the difficulties of being involved in an incident like this is communicating to outsiders that you are all right. I didn’t have an international-capable cell phone, and it took some time before I was able to grab a satellite phone. I got through to my mother I remember, but not Ariel. Meanwhile, my father, who by then was remarried to someone who had worked for the British Foreign Office, was also frantic. His wife found out from her contacts that there was a running total of 15 dead (the total was 22 dead and 150 wounded), but nothing more.

Quick reference to another video:

North-West Namibia: maybe the most special landscape area I ever had the luck to film in:

“Namibia’s Black Rhino: their last wild retreat” https://vimeo.com/170677131

Fast and furious, or slow and intriguing?

This is an issue that’s definitely relevant to our video-making – but I’ll also digress a little, just for the hell of it.

Is fast editing always a good thing? I don’t think so. Lemme make a comparison – between two action sequences – one is from 1968, the “Bullitt” car chase sequence, and one is from the car chase sequence in the Bond move “Quantum of Solace” from 2008 – 40 years later. This is subjective – but which do you prefer?

Quantum of Solace:

Bullitt:

I prefer Bullitt for a number of reasons: it gives you time to locate the cars and their positions both in relation to each other and within the landscape; it creates a sequence of human reactions and expressions that are part of the drama; it takes time to build suspense and twists; it breaks from music, to just squealing tyres, to good effect – so it uses changes in dynamics, human character, and above all you know where everything is. You are located, concretely involved in the chase, you can feel it and sense it, and this is achieved through using longer shots and a slower editing pace.

Whereas I think the Quantum of Solace sequence is merely very fast editing overused to no good effect. I don’t think you get a good sense of where and how things are happening – you don’t even know who is who, much of the time; you don’t get a relatedness to human beings, and you don’t get any sense of suspense – there is no change in dynamics, just continual, fast-cut action. To me this is very much inferior to the 1968 version of a car chase. Fast editing is used here to try to create excitement, but actually produces less excitement, because of the reduced relatedness and physical locatedness.

I am not against fast editing – but it has to be used in the right place and at the right time. And sure, as current trends go, you probably do need a quick grabbing soundbite or action right at the beginning of a YouTube product.

But after that, if your material is powerful, you probably don’t need fast, slick editing. The film director Jules Dassin (director of 1951 film noir “Night and the City” 1951, one of my favourite movies) said that “interest equals pace.” In other words, if an audience is gripped and engaged by the material, they don’t need to be chivvied along with fast editing – they are already there. In fact, fast editing will actually reduce the effectiveness.

An example of a “slow” film: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=wUVHzMgbW4I

This is the trailer from the 2020 film “After Love” about a British Muslim woman who discovers her husband has had a relationship with a French woman across the English Channel. Unfortunately, I can’t access the full film – but it starts with an extraordinary scene (not included here sadly). There is a single shot from a fixed camera position. Neither character on screen approaches very close to the camera and the action unfolds over several minutes. I like slow, but even for me I was just beginning to wonder…but the film, I think, is amazing, with great and surprising drama. It gives its actors time to act – and we have time to feel the story. For this film, slowness is all and interest definitely equals pace.

Again, fast editing can be effective at the right time and place, but don’t overuse it, and I don’t agree with the proposal that fast editing = a good piece.

Summing up

Overall, for me, it’s always the story that’s most important – by far. It’s not the cool graphics, or elegant fonts, great camera, or groovy template. It’s the story – it’s the human beings and it’s the emotionof human beings, and wondering what they will do next.

If there’s one word I’d want to emphasise, besides story, it’s emotion. That is what you are looking for in any in-depth film that involves people. Emotion, emotion, emotion. It’s what grips people, engages them, doesn’t let them go, gives them an experience and, also, has them think and react, and renders them more likely to be influenced. That, primarily, is what we are seeking at UN Video.

So when it comes to your characters, let ‘em speak and let ‘em do.

So keep on keeping on – telling great stories for the UN. It’s worth it.

You can find many of my films on my vimeo site: https://vimeo.com/channels/francischannel

I’m currently archiving some of my films for the UN from the above list, and I came across this one which, I hope, shows the emotion of a Syrian woman – who had to flee to Berlin, and is thriving – but still misses her home country:

Leave a comment